Introduction

Criminology and penology, as fields of study, critically examine the causes of crime and the systems designed for its control, punishment, and prevention. Central to penology is the concept of sentencing philosophy, which underpins the objectives and methods of penal systems worldwide. Historically, four primary philosophies have dominated discussions: retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation. While each offers a distinct rationale for state-imposed punishment, their prominence has waxed and waned, reflecting societal values, scientific understanding, and political climates. This article will critically examine the evolution of these philosophies, with a particular focus on rehabilitation – its historical ascendancy, its period of decline, and its contemporary challenges and potential for resurgence within modern penal systems. The central argument is that while rehabilitation offers a humane and potentially effective approach to reducing recidivism and fostering social reintegration, its implementation faces significant hurdles in modern penal policy, often overshadowed by more punitive paradigms.

The Historical Trajectory of Sentencing Philosophies

Early penal systems were largely characterized by **retribution**, an “eye for an eye” approach focused on proportionate punishment for moral wrongdoing. This philosophy, rooted in classical legal thought, posits that punishment should be administered because an offense was committed, serving to restore moral balance. Concurrent with retribution, **deterrence** emerged as a utilitarian objective, aiming to prevent future crimes either by specific deterrence (discouraging the offender) or general deterrence (discouraging others through the offender’s punishment). Thinkers like Jeremy Bentham and Cesare Beccaria championed these ideas, emphasizing the rational actor and the calculus of pain and pleasure.

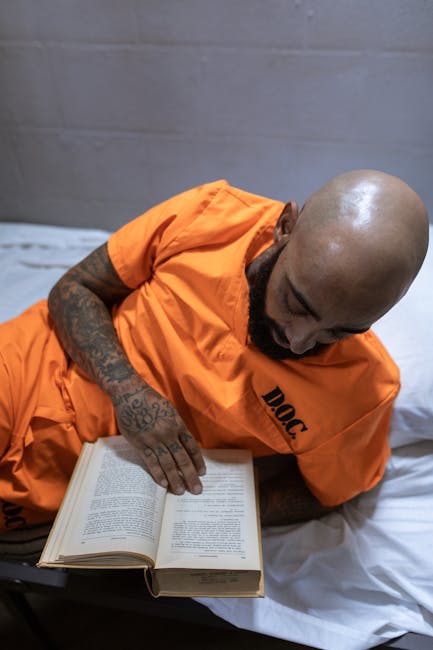

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a significant shift with the rise of the **rehabilitative ideal**. Influenced by the positivist school of criminology, which sought to understand the root causes of criminal behavior rather than merely punishing the act itself, rehabilitation proposed that offenders could be reformed and reintegrated into society. This philosophy gained significant traction, leading to the development of indeterminate sentencing, parole, probation, and various correctional programs aimed at education, vocational training, and psychological treatment. The focus shifted from the crime to the criminal, with the goal of “curing” the underlying pathologies believed to cause criminality. This era saw the widespread adoption of correctional institutions designed not merely for custody but for reform, embodying a more optimistic view of human potential for change.

The fourth major philosophy, **incapacitation**, found its footing in the recognition that some offenders, regardless of rehabilitation efforts, pose an ongoing threat to public safety. This philosophy advocates for the removal of such individuals from society, typically through incarceration, to prevent them from committing further crimes. While present throughout history, incapacitation gained significant prominence later, often in conjunction with other aims.

The “Nothing Works” Era and its Legacy

The rehabilitative ideal, despite its initial promise, faced considerable criticism and a subsequent decline in influence by the mid-1970s. A pivotal moment was the publication of Robert Martinson’s 1974 report, “What Works?–Questions and Answers About Prison Reform,” which famously concluded that “with few and isolated exceptions, the rehabilitative efforts that have been reported so far have had no appreciable effect on recidivism.” While Martinson later nuanced his findings, the sensationalized interpretation of “nothing works” provided powerful ammunition for critics of rehabilitation.

This era coincided with rising crime rates in many Western nations, particularly the United States, fostering a societal demand for “tough on crime” policies. The perceived failure of rehabilitation, coupled with anxieties about public safety, led to a dramatic pendulum swing towards more punitive approaches. **Retribution** and **incapacitation** became the dominant paradigms, manifesting in policies such as mandatory minimum sentencing, three-strikes laws, and the abolition of parole in many jurisdictions. Indeterminate sentencing, once a hallmark of the rehabilitative model, was largely replaced by determinate sentencing schemes, often guided by strict guidelines that limited judicial discretion to consider rehabilitative potential. The focus shifted back to punishment and crime control, leading to a significant expansion of prison populations, particularly in the United States, which became the world leader in incarceration rates.

Contemporary Challenges and the Resurgence of Rehabilitative Ideals

The legacy of the “nothing works” era, characterized by mass incarceration and high recidivism rates, has prompted a critical re-evaluation of purely punitive approaches. The economic burden of burgeoning prison systems, coupled with stagnant or rising recidivism, has rekindled interest in rehabilitation. Modern research, employing more rigorous methodologies, has challenged Martinson’s original sweeping conclusion, identifying various evidence-based rehabilitative programs that *do* work.

Today, the challenges to rehabilitation are multifaceted. Politically, “tough on crime” rhetoric often remains popular, making it difficult to advocate for programs perceived as “soft” on offenders. Resource allocation is another major hurdle; effective rehabilitative programs, particularly those addressing complex issues like addiction, mental illness, and lack of education/vocational skills, require substantial funding and highly trained personnel. Public perception, often shaped by media portrayals of crime, can also be resistant to efforts aimed at offender reintegration.

Despite these challenges, there is a growing recognition that a purely punitive approach is unsustainable and often counterproductive. Many jurisdictions are witnessing a resurgence of rehabilitative ideals, albeit often under new terminologies like “re-entry initiatives” or “evidence-based corrections.” The First Step Act, signed into law in the United States in 2018, exemplifies this trend at the federal level, expanding rehabilitative programming in federal prisons and offering pathways to reduced sentences for eligible inmates. This act, along with a proliferation of drug courts, mental health courts, and problem-solving courts, represents a pragmatic shift, acknowledging that addressing the root causes of criminal behavior through targeted interventions can ultimately enhance public safety and reduce long-term costs. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), educational programs, and vocational training are now widely recognized as effective tools for reducing recidivism when properly implemented and maintained.

The current landscape demands a more balanced approach, one that integrates the legitimate aims of public safety and accountability with the transformative potential of rehabilitation. Jurisdictions like Norway and other Nordic countries, which prioritize reintegration and maintaining community ties, often demonstrate significantly lower recidivism rates compared to more punitive systems, offering a compelling comparative model for the efficacy of a rehabilitation-focused approach.

Conclusion

The journey of sentencing philosophies reflects a continuous societal negotiation between the impulses of retribution and the aspirations of reform. While retribution, deterrence, and incapacitation play undeniable roles in any just penal system, the rehabilitative ideal remains a crucial, if often challenged, component. The “nothing works” era, born from specific historical and research contexts, led to a period of heightened punitiveness with unintended consequences, including mass incarceration and its associated social and economic costs.

However, contemporary penology is witnessing a renewed, evidence-based embrace of rehabilitation. This resurgence is driven by the pragmatic realization that effective crime control involves not just punishment but also the successful reintegration of offenders into society. The challenges remain significant, particularly in terms of political will, public acceptance, and sustained funding. Nevertheless, the future of penology lies in a balanced, intelligent synthesis of all sentencing philosophies, with a critical, renewed emphasis on the transformative and recidivism-reducing potential of rehabilitation. By investing in programs that address the underlying causes of crime and equip offenders with the tools for a productive life, societies can move towards more effective, humane, and sustainable systems of justice.

About the Author:

Burak Şahin is an attorney registered with the Manisa Bar Association. He earned his LL.B. from Kocaeli University and is pursuing an M.A. in Cinema at Marmara University. With expertise in Criminology & Penology, he delivers interdisciplinary legal analysis connecting law, technology, and culture. Contact: mail@buraksahin.av.tr