**Abstract:** Traditional retributive justice systems, focused primarily on punishment and deterrence, frequently fall short in addressing the holistic needs of victims, offenders, and communities. This article explores restorative justice as a transformative paradigm in penology, offering a robust alternative to conventional punitive approaches. By emphasizing the repair of harm, direct engagement among stakeholders, and the reintegration of offenders, restorative justice challenges the core tenets of retribution and deterrence. Through an examination of its foundational principles, practical applications, and demonstrated benefits, alongside inherent challenges, this article argues that integrating restorative justice more broadly into legal frameworks can foster a more humane, effective, and community-centered approach to crime and conflict resolution.

**Introduction**

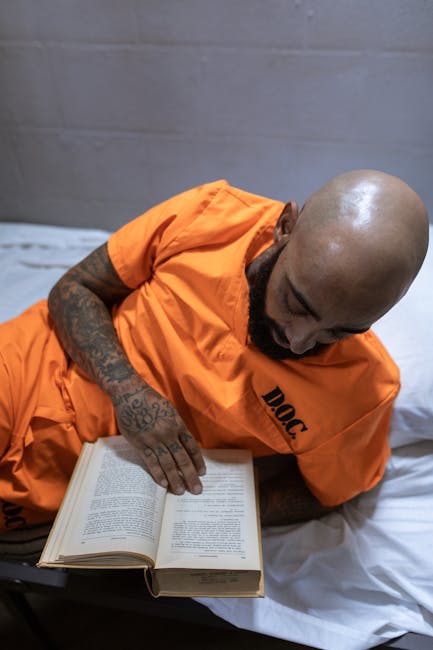

The prevailing model of criminal justice in many jurisdictions is predicated on retribution: the notion that an offender must suffer a penalty commensurate with the harm inflicted, coupled with the aims of deterrence and incapacitation. This retributive paradigm, deeply entrenched in legal systems globally, often operates under the assumption that state-sanctioned punishment is the most effective means to address crime, ensure public safety, and satisfy the demands of justice. However, despite vast investments in penal institutions and punitive measures, high rates of recidivism, persistent victim dissatisfaction, and pervasive systemic inequalities signal a fundamental deficiency in this traditional approach (Braithwaite, 1989).

In response to these shortcomings, the principles and practices of restorative justice (RJ) have emerged as a significant counter-narrative, proposing a radical shift in how societies understand and respond to crime. Rather than asking “What law was broken? Who did it? What punishment is deserved?”, restorative justice reframes the inquiry to “Who has been harmed? What are their needs? Whose obligations are these?” (Zehr, 2002). This article argues that restorative justice represents a critical paradigm shift in penology, moving beyond the limitations of retribution to foster healing, accountability, and community repair. It will delve into the theoretical underpinnings of RJ, explore its diverse applications, weigh its benefits against its challenges, and ultimately advocate for its broader integration into contemporary justice systems.

**The Foundations of Restorative Justice: Repairing Harm**

At its core, restorative justice is a philosophy and a set of practices that seek to repair the harm caused by crime and conflict. Unlike retributive justice, which views crime primarily as a violation of state law, RJ perceives crime as a violation of people and relationships. This fundamental difference reorients the justice process from an adversarial state-versus-offender dynamic to a collaborative, multi-stakeholder endeavor involving victims, offenders, and affected communities.

Key principles underpin the restorative framework:

1. **Repairing Harm:** The primary goal is to address and, where possible, repair the physical, emotional, and social harms resulting from crime.

2. **Voluntary Participation:** All parties engage willingly, ensuring genuine dialogue and empowerment.

3. **Inclusion of Stakeholders:** Victims, offenders, and community members are actively involved in determining how to respond to the crime and its consequences.

4. **Encounter:** Providing opportunities for victims and offenders to meet (if appropriate and desired) to discuss the crime, its impact, and what needs to be done to make things right.

5. **Accountability:** Offenders take responsibility for their actions, understand the impact of their behavior, and actively participate in repairing the harm.

6. **Reintegration:** Both victims and offenders are supported in their reintegration into the community, reducing the likelihood of future harm.

Influential theorists such as John Braithwaite (1989), with his concept of “reintegrative shaming,” and Howard Zehr (2002), a pioneer in defining restorative justice, have significantly shaped this understanding. Braithwaite posits that shaming, when followed by efforts to reintegrate the offender, can be a powerful force for crime reduction, distinguishing it from stigmatizing shaming that merely marginalizes. Zehr emphasizes the need for a victim-centered approach, focusing on their needs for information, truth, restitution, and a sense of safety.

**Practical Applications and Mechanisms**

Restorative justice is not a singular program but encompasses a variety of practices tailored to different contexts and types of offenses. Some of the most widely adopted mechanisms include:

* **Victim-Offender Mediation (VOM):** Facilitated dialogues between victims and offenders, typically after a crime, to discuss the incident, its impact, and potential ways to repair the harm. These programs are common in North America and Europe, often addressing property crimes or minor assaults.

* **Family Group Conferencing (FGC):** Originating in New Zealand, FGC involves a broader circle of stakeholders, including family members, support persons, and community representatives, in addition to the victim and offender. The New Zealand Youth Justice System, governed by the Children, Young Persons and Their Families Act 1989, is a global exemplar, demonstrating the effectiveness of FGCs in diverting young offenders from traditional courts and reducing re-offending rates.

* **Sentencing Circles:** Predominantly used in Indigenous justice systems in Canada and Australia, sentencing circles bring together the victim, offender, their families, elders, and community leaders to collaboratively determine an appropriate response to crime. These circles are deeply rooted in Indigenous cultural traditions of conflict resolution and healing, often focusing on spiritual and community repair beyond legalistic sanctions. The Canadian Supreme Court’s *Gladue* principles, requiring courts to consider the unique circumstances of Indigenous offenders, implicitly encourage such restorative and culturally appropriate sentencing alternatives.

* **Restorative Justice Dialogue (RJD):** Applied in more serious cases, even involving violent crime, RDJs bring together victims and offenders (sometimes years after the crime) with highly trained facilitators to foster understanding, accountability, and healing.

These applications demonstrate RJ’s versatility, moving beyond punitive measures to create spaces for meaningful dialogue and constructive solutions. They can be implemented at various stages of the criminal justice process: pre-charge diversion, pre-sentence alternatives, or post-conviction reconciliation.

**Benefits and Challenges of Restorative Justice**

The burgeoning evidence base for restorative justice highlights its potential to yield significant benefits for all parties involved:

* **For Victims:** RJ processes offer victims agency, a voice in the justice process, answers to their questions, and an opportunity to express their pain and needs directly to the offender. Studies indicate that victims participating in RJ programs report higher satisfaction rates with the justice process and a greater sense of healing and closure compared to those in traditional courts (Sherman & Strang, 2011).

* **For Offenders:** RJ provides offenders with an opportunity to understand the impact of their actions, take genuine responsibility, express remorse, and make amends. This active accountability often leads to increased empathy, reduced anger, and lower rates of recidivism compared to incarceration alone. Meta-analyses, such as those conducted by Latimer, Dowden, and Muise (2005), suggest that RJ programs can lead to modest but significant reductions in re-offending.

* **For Communities:** Restorative practices strengthen communities by fostering dialogue, promoting conflict resolution skills, and building capacity for collective problem-solving. They reduce reliance on the state for punishment, empowering communities to address internal conflicts and reintegrate members.

Despite these compelling advantages, restorative justice faces several challenges to widespread adoption:

* **Systemic Resistance:** Traditional justice systems, deeply invested in retributive frameworks, often resist the fundamental shifts required by RJ. This resistance manifests in a lack of funding, training, and institutional support.

* **Scope and Suitability:** Concerns exist regarding the applicability of RJ to all types of offenses, particularly severe violent crimes, and its potential to re-victimize participants if not carefully managed. Ensuring power imbalances are addressed and participation is genuinely voluntary is critical.

* **Measuring Success:** While qualitative benefits like healing and empathy are evident, quantifying the success of RJ in purely statistical terms can be challenging, as its goals extend beyond mere reductions in recidivism.

* **Co-optation Risk:** There is a risk that RJ principles might be co-opted by state institutions, losing their transformative edge and becoming another tool for control rather than genuine restoration (Pavlich, 2005).

**Integrating Restorative Justice into the Broader Penological Framework**

The future of penology lies not in the wholesale abandonment of traditional justice but in a strategic integration of restorative principles. RJ should be viewed not as a complete replacement for the established legal system but as a vital complementary approach that can operate at various points along the justice continuum. Diversion programs at the pre-charge stage, restorative options within sentencing, and post-conviction victim-offender dialogues all present opportunities to leverage the strengths of RJ.

Achieving this integration requires robust legislative and policy support, comprehensive training for legal professionals, and increased public awareness. The experience of jurisdictions like New Zealand and various Indigenous communities demonstrates that with political will and cultural sensitivity, restorative approaches can flourish and significantly contribute to a more just and humane society. By embracing RJ, legal systems can shift their focus from merely punishing past wrongs to actively repairing harm, building community resilience, and fostering genuine accountability and reintegration.

**Conclusion**

Restorative justice offers a profound and necessary paradigm shift in penology. By re-centering the justice process on the needs of victims, the accountability of offenders, and the healing of communities, it provides a compelling alternative to the limitations of retribution. While challenges remain in its broader implementation and institutional acceptance, the demonstrated benefits—including increased victim satisfaction, reduced recidivism, and strengthened community bonds—underscore its transformative potential. Moving forward, a balanced approach that strategically integrates restorative practices within existing legal frameworks holds the key to developing a more effective, compassionate, and truly just response to crime and conflict, paving the way for a penology that prioritizes healing over hurting, and restoration over mere retribution.

**References (Illustrative):**

* Braithwaite, J. (1989). *Crime, Shame and Reintegration*. Cambridge University Press.

* Children, Young Persons and Their Families Act 1989 (New Zealand).

* Latimer, J., Dowden, I., & Muise, D. (2005). *The Effectiveness of Restorative Justice Practices: A Meta-analysis*. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice Canada.

* Pavlich, G. C. (2005). *Restorative Justice and the Limits of Communitarianism*. University of British Columbia Press.

* Sherman, L. W., & Strang, H. (2011). *Restorative Justice: The Evidence*. The Smith Institute.

* Zehr, H. (2002). *The Little Book of Restorative Justice*. Good Books.

About the Author:

Burak Şahin is an attorney registered with the Manisa Bar Association. He earned his LL.B. from Kocaeli University and is pursuing an M.A. in Cinema at Marmara University. With expertise in Criminology & Penology, he delivers interdisciplinary legal analysis connecting law, technology, and culture. Contact: mail@buraksahin.av.tr