Introduction

The question of how society ought to respond to criminal behavior lies at the heart of criminology and penology. For centuries, legal systems have grappled with the dual objectives of punishing offenders and fostering societal safety. This enduring dilemma has given rise to diverse theoretical frameworks and practical applications, primarily characterized by two dominant, often opposing, paradigms: retributive justice and restorative justice. While retributive models prioritize punishment commensurate with the gravity of the offense, aiming to uphold moral order and deter future transgressions, restorative approaches seek to repair the harm caused by crime, engaging victims, offenders, and communities in a process of healing and reintegration. This article critically examines the theoretical underpinnings and practical efficacy of these two models, arguing for a nuanced, integrated approach that leverages the strengths of both to address the complexities of modern criminal justice systems more effectively and equitably.

Retributive Justice: Foundations and Critiques

Retributive justice, historically the bedrock of most Western penal systems, is predicated on the principle that punishment should be proportionate to the harm caused by the crime. Its intellectual roots trace back to ancient concepts of *lex talionis* (“an eye for an eye”) and later, to philosophical justifications advanced by Immanuel Kant and G.W.F. Hegel, who viewed punishment as a moral imperative necessary to restore the equilibrium of justice disrupted by the criminal act. From a Kantian perspective, punishment is a categorical imperative, an end in itself, owed to the offender for their transgression, irrespective of its utilitarian benefits such as deterrence or rehabilitation. This “just deserts” model, popularized by Andrew von Hirsch, emphasizes that the severity of punishment should be scaled to the seriousness of the crime and the culpability of the offender (von Hirsch, 1987).

In practice, retributive justice manifests through structured sentencing guidelines, mandatory minimums, and a primary focus on the offender’s past actions. The United States Supreme Court, in *Gregg v. Georgia*, 428 U.S. 153 (1976), explicitly recognized retribution as a legitimate purpose of criminal punishment, alongside deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation. Contemporary penal codes across various jurisdictions reflect this by prescribing fixed or ranges of penalties for specific offenses, aiming for consistency and proportionality. For instance, the Federal Sentencing Guidelines in the United States, while attempting to standardize sentencing, often embody a retributive philosophy by tying penalties directly to offense severity and criminal history.

However, the retributive paradigm faces significant critiques. While it provides a clear moral framework for holding individuals accountable, its efficacy in achieving broader societal goals, such as crime reduction or victim satisfaction, is debatable. Critics argue that a sole focus on punishment often neglects the root causes of criminal behavior, contributes to high recidivism rates, and can perpetuate cycles of violence and marginalization (Garland, 2001). Furthermore, the adversarial nature of retributive processes often marginalizes victims, reducing their role to that of a witness, and fails to address their emotional, psychological, or material needs for recovery. The astronomical costs associated with mass incarceration, particularly in countries like the United States, also highlight the practical limitations and societal burdens of a predominantly retributive system.

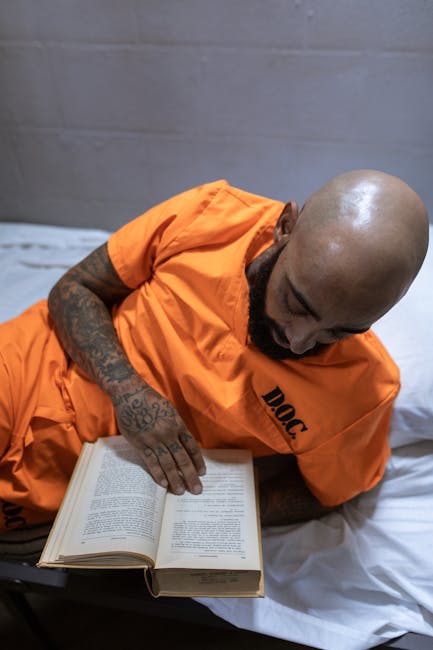

Restorative Justice: Principles and Promise

In contrast, restorative justice offers an alternative paradigm, shifting the focus from “what law has been broken?” to “who has been harmed and what needs to be done to repair that harm?” Originating from Indigenous justice practices and gaining prominence in the late 20th century, restorative justice views crime primarily as a violation of people and relationships, rather than solely a transgression against the state (Zehr, 2002). Its core principles include repairing harm, offender accountability through understanding impact, victim empowerment, and community involvement in resolving conflict.

Key restorative practices include victim-offender mediation (VOM), family group conferencing (FGC), and circle sentencing. These processes typically bring together victims, offenders, and relevant community members in a structured dialogue, facilitated by a neutral party, to discuss the crime’s impact, formulate a plan for reparation (e.g., restitution, community service, apology), and facilitate the offender’s reintegration. One of the most prominent examples of a state-sanctioned restorative justice system is New Zealand’s youth justice framework, established by the *Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989*. This legislation mandates family group conferences for most young offenders, significantly reducing reliance on formal court processes and incarceration for youth. Similar initiatives have been adopted in Canada, particularly within Indigenous communities, and in various pilot programs across Europe and the United States.

The promise of restorative justice is multi-faceted. Research suggests that restorative practices can lead to higher victim satisfaction, reduced fear among victims, and increased feelings of safety (Sherman & Strang, 2011). For offenders, it can foster genuine remorse, a deeper understanding of the consequences of their actions, and increased motivation for desistance from crime. Studies have also indicated lower recidivism rates among offenders who participate in restorative programs compared to those in traditional systems, particularly for less serious offenses. Moreover, by involving the community, restorative justice aims to strengthen social bonds and build collective responsibility for addressing crime and its aftermath.

Comparative Analysis and Challenges

While seemingly antithetical, both paradigms offer distinct values. Retribution provides a clear societal statement that certain acts are intolerable and demands accountability, thereby affirming moral boundaries and the rule of law. Restorative justice, on the other hand, focuses on healing and preventing future harm by addressing underlying issues and fostering empathy.

However, each model presents unique challenges. For restorative justice, its applicability to all types of crime, particularly serious violent offenses, remains a subject of debate. Concerns exist regarding potential re-victimization if not managed carefully, resource intensity, and scalability across diverse legal and cultural contexts. The voluntary nature of participation also means it may not be suitable for all offenders or victims. Conversely, while retribution provides a sense of “just deserts,” its emphasis on punishment alone often fails to equip offenders with the tools for successful reintegration, contributing to high rates of recidivism and the immense social and economic costs of maintaining large carceral populations.

Towards an Integrated Paradigm

The future of penology likely lies not in the wholesale abandonment of one model for another, but in the intelligent integration of their respective strengths. A truly effective and just criminal justice system would acknowledge the legitimate need for accountability and proportionate sanctions (retributive elements) while simultaneously prioritizing the repair of harm, victim empowerment, and offender rehabilitation (restorative elements).

Such an integrated approach might entail:

1. **Tiered Responses:** Employing restorative practices as a primary response for less serious offenses and for juvenile justice, with retributive sanctions reserved for serious violent or repeat offenses.

2. **Hybrid Programs:** Incorporating restorative components, such as victim impact statements or opportunities for mediation, within traditionally retributive sentencing frameworks. Many jurisdictions already allow for restitution as part of sentencing, which has restorative dimensions.

3. **Emphasis on Rehabilitation:** Reinvesting in robust rehabilitation programs within correctional facilities, focusing on education, vocational training, and mental health support, which are crucial for offender reintegration and recidivism reduction, aligning with the restorative goal of making offenders productive community members.

4. **Community Engagement:** Fostering greater community involvement in crime prevention, diversion programs, and post-release support, thereby strengthening the social fabric that both models ultimately seek to protect.

The challenge lies in designing legal frameworks and policy mechanisms that can seamlessly blend these approaches, ensuring that the pursuit of justice is both firm in its resolve against crime and compassionate in its effort to heal individuals and communities.

Conclusion

The paradigms of retributive and restorative justice represent two fundamental responses to criminal behavior, each with distinct philosophical foundations, practical applications, and inherent limitations. While retribution serves to uphold the rule of law and assign deserved blame, it often falls short in addressing the holistic needs of victims and fostering offender reintegration. Restorative justice, conversely, excels in repairing harm and building community, but faces challenges regarding scalability and applicability to all offenses.

Moving forward, an enlightened penological approach necessitates a move beyond a binary choice. By carefully integrating elements from both models – recognizing the necessity of accountability while prioritizing healing, reconciliation, and rehabilitation – legal systems can aspire to achieve a more comprehensive, humane, and ultimately more effective response to crime. The enduring dilemma of justice demands not a simple solution, but a complex, nuanced strategy capable of navigating the intricate landscape of harm, responsibility, and societal well-being.

References

* Garland, D. (2001). *The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society*. University of Chicago Press.

* *Gregg v. Georgia*, 428 U.S. 153 (1976).

* Sherman, L. W., & Strang, H. (2011). *Restorative Justice and Recidivism: The Results of the Canberra Reintegrative Shaming Experiments (RISE)*. Springer.

* von Hirsch, A. (1987). Doing Justice: The Principle of Commensurate Deserts. *Journal of Applied Philosophy*, 4(1), 11-20.

* Zehr, H. (2002). *The Little Book of Restorative Justice*. Good Books.

About the Author:

Burak Şahin is an attorney registered with the Manisa Bar Association. He earned his LL.B. from Kocaeli University and is pursuing an M.A. in Cinema at Marmara University. With expertise in Criminology & Penology, he delivers interdisciplinary legal analysis connecting law, technology, and culture. Contact: mail@buraksahin.av.tr